We looked at parental concerns when it comes to online learning and how effective they feel parental controls are in tackling those concerns.

A PDF version of this report is available. We also created an accompanying infographic in both booklet and scrolling formats.

[lwptoc]

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

We looked at the complex world of parental controls in response to an explosion of online learning as a result of the current COVID-19 pandemic: an estimated 1.2 billion children have been required to carry out some kind of online learning in 2020.

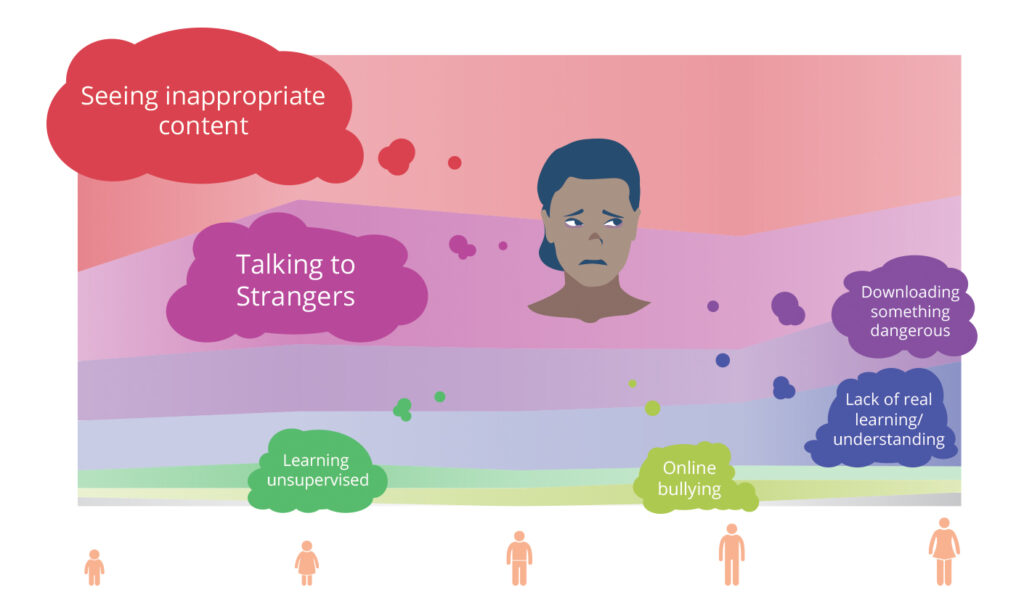

A majority of parents use parental controls to deal with their concerns over what remains a largely unsupervised activity. By far the greatest concern across all age groups is that children will see inappropriate content, followed by talking to strangers. But there were a number of other significant concerns, which varied widely depending on the age of the child.

The absence of standards in both software and terminology, combined with a huge array of devices, apps and services, has created a level of complexity in the parental controls market that defies easy explanation. Parental controls are not static and change constantly as technology companies update their software. This has the knock-on impact that guides to parental controls quickly become outdated. Such changes have been especially significant in recent months as a result of the huge increase in online learning.

Parental controls are not static and change constantly as technology companies update their software.

Despite this, most parents report being happy with their ability to control for their largest concerns, even if they can quickly and easily identify problems and improvements in the controls they use. Parental controls are only a partial solution, however: it is critical for parents and teachers to educate children on how to learn safely online.

We surveyed over 1,000 parents in the United States and United Kingdom and built a comprehensive picture of online learning and parental controls for different age groups. While the largest patterns – watching videos and inappropriate content – were largely the same across all age groups, there were distinct use cases within each age group that demand closer attention. As examples: the increased risk of online bullying through chat apps among 11-13 year-olds; and the lack of confidence in parental controls on mobile phones.

We produced an infographic to accompany our findings and hope to provide both parents and policymakers with a better understanding of what online learning looks like and what they can do to make it safer for children who will be undertaking far more online learning now and in future, in situations where they will be less supervision than if they were in a physical classroom.

INTRODUCTION

The arrival of a coronavirus pandemic in early 2020 led to an explosion in the use of online learning across the globe as an estimated 1.2 billion children[efn_note]https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse[/efn_note] of all ages were required to stay at home as schools closed in an effort to contain the virus.

As we have gone past the summer holidays and into the new school year, many children will still need to take many or most of their classes online. Even before COVID-19, however, there was high growth and adoption in new education technology that makes use of the internet to allow for remote or distance e-learning – and that trend looks set to continue.

There are many different aspects to a shift to online learning including the availability of fast internet access and learning devices, changes in teaching styles and approaches, and software solutions to provide an effective learning experience.

We decided to look at a key social aspect of online learning: parental concerns and efforts to alleviate them by using software controls. To that end, we developed an online survey comprising 22 inter-related questions and approached parents in both the United States and the United Kingdom for their experiences.

Over the course of June 2020, we received 1,173 responses; 707 of them from the US and the remainder, 466, from the UK. We are confident this represents a statistically relevant and representative sample of parents in both countries[efn_note]More details on the full breakdown of those surveyed is available further on in this report[/efn_note].

This report details the results of that survey, complete with an analysis of the current

situation as it relates to online learning and parental controls, as well as some pointers for additional research and recommendations for improvement. We have also produced an accompanying infographic to make the results more readily digestible.

If you any comments or questions on this report, our approach, methodology or conclusions please feel free to contact IFFOR at the email address info@iffor.org or through our online contact form.

THE BIG PICTURE

It is worth noting that when we started out on this policy work, we did not have a tightly defined approach but wished to look at the overall topic of online learning with an eye to developing something that was both informative and pragmatic primarily for parents but also for policymakers and schools.

It quickly became apparent that the topic was more complex than initially anticipated. The activities that comprise online learning are relatively clear and well-defined. For many of those tasks e.g. live video lessons there are also a few main companies whose services and software dominate the market – with the exception of the educational app market, which is diverse in comparison.

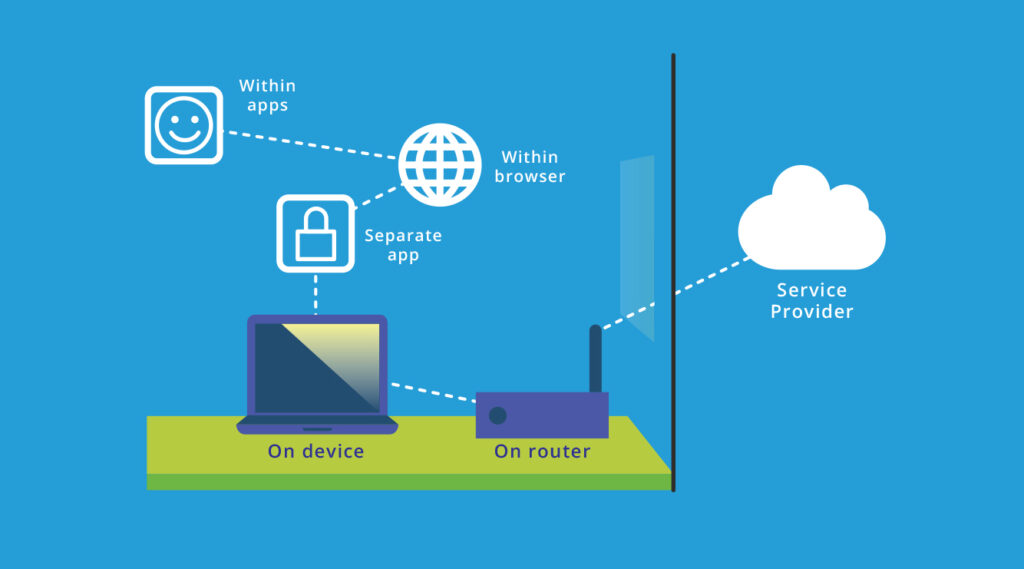

However, when it comes to parental controls, the picture is so large and complex that it largely defies any effort to produce a pragmatic guide. While there is a relatively small group of user devices – laptops, tablets, mobile phones and desktop computers – those devices are manufactured by a large number of companies and run different operating systems. Many parents use standalone parental control apps or software.

In addition, parental controls exist in hardware and software outside the user device: an internet router that connects to the internet is its own device and will often its own system for controlling content. Likewise internet service providers and mobile operators will also offer parental controls.

There are also no agreed standards, or even terminology, over parental controls, making comparisons even more difficult.

An initial review of the parental controls ecosystem produced 13 different categories of companies that offer options, seven different areas where controls are offered, and 22 different types of controls.

That already complex situation is then compounded by the fact that many controls are effectively cumulative: controls at the ISP level will take effect before content even reaches the device. Content will then pass through a router (on which there may be controls), then the device’s operating system, then any standalone control app, before it even hits the controls within a given app or service.

That means one set of controls will impact and can interfere with another. Again, with no agreement over how to approach controls, or standards, or even common language between companies, it is simply impossible to predict what any given parent’s needs and issues will be.

Existing guides

Despite the complexity, there are numerous guides available online – some produced by the companies behind the controls, others by independent third parties – that attempt to guide parents through how to apply the right controls for them.

We investigated whether it would be worthwhile producing an online reference to these guides, categorizing them in a useful manner and highlighting the most useful or comprehensive examples. However it quickly became clear that there is another problematic component to parental controls: they are constantly changing.

Technology companies, particularly large companies like Google, Apple, Facebook and so on, regularly update their software and when they do, they frequently change controls at the same time. Not only does language change but also the location of any settings and often the impact of the control itself.

As a result, most online guides to parental controls are out of date almost as soon as they are published – and grow increasingly stale over time. Any guide that we produced would itself capture only a moment in time and would require constant updating to stay relevant.

Parental focus

Faced with that reality, we decided to concentrate on a broader picture and use parents’ own experience to understand it, which led to our survey. The survey was designed to identify what sort of activities children of different ages engage in while online learning and on what devices. Then we asked parents what their concerns are, what controls they use, and how satisfied they are with those controls.

We have put a copy of the survey at the end of this report. It should be noted that the survey was carried out online and contained internal question logic so some questions were only seen in response to answers to previous questions i.e. if a parent didn’t select “chat” as an online activity, they didn’t see the question asking what type of chat software their child used.

The survey produced a wealth of data and insights that we have tried our best to relay here and in the accompanying infographic.

One thing we should specifically note, since it is not immediately clear from the results, is that despite the extraordinarily complex current reality of parental controls, parents are, on the whole, fairly happy with them.

We were expecting the opposite to be true – a flood of horror stories and angry complaints – and we were expecting to be able to recommend some controls and warn people away from others. But the truth is more complex. While there is definite room for improvement (which we cover briefly below), parents have tended to find an approach that works for them.

The key insights that we can often then comprise of recognizing that there are clear patterns in online learning activity, patterns that change as a child grows older. Within those patterns there are also distinct issues and behaviors that parents have noted through experience are more relevant to their child as they grow up.

By recognizing and highlighting what those patterns are, we hope to provide both parents and, potentially, policymakers within and outside technology companies, with a better understanding of what online learning looks like and what they can do to make it safer for children who, through necessity, will be under less supervision than if they were in a physical classroom.

SURVEY RESULTS: Across all age groups

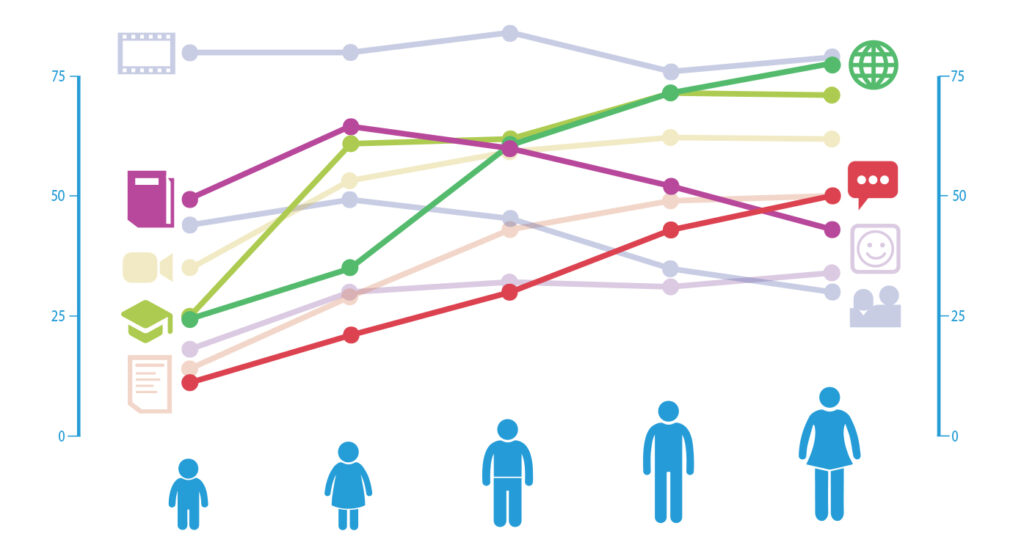

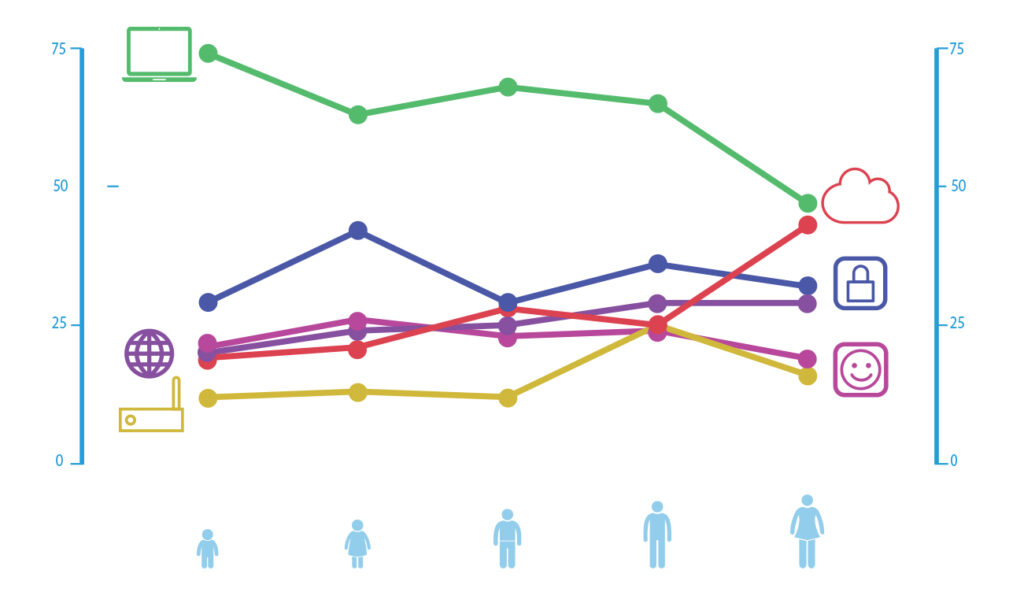

When we analyzed our survey results, it quickly became clear that the best way to understand them was through different age groups, identifying trends and patterns both within specific age groups and across all age groups. In this case, we separated children into five age groups: under 5s, ages 5-7, 8-10, 11-13, and 14+.

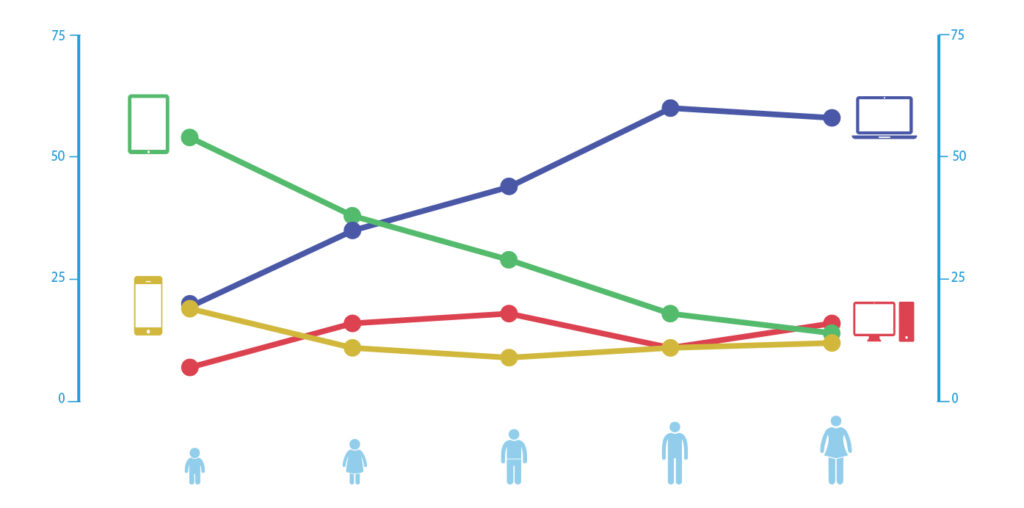

Device usage

Device usage changes significantly as a child matures. There is a clear shift from tablets with touch screens in younger children to laptops with keyboards in older children with the key crossover point between 5 and 7. A significant number however use both desktops and mobile phones as their primary learning device.

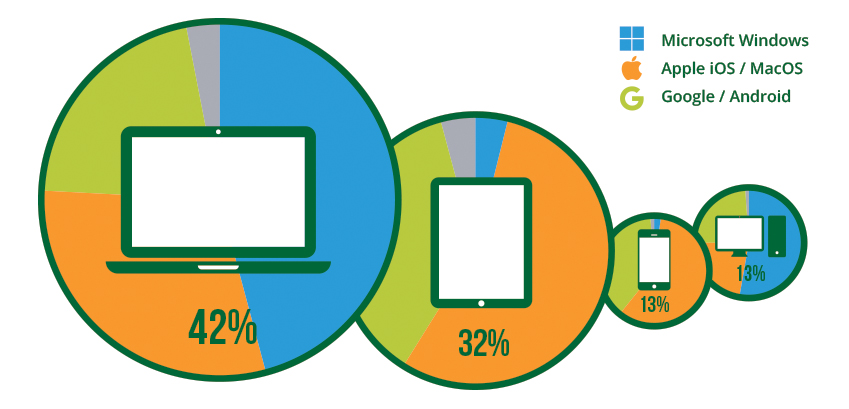

Software usage: operating system

Device operating systems are dominated by the three largest tech companies: Apple, Google and Microsoft. The majority of tablets used by children have the Apple’s iOS operating system i.e. are iPads; the majority of laptops use Microsoft’s Windows, although Google Chromebooks are also popular; mobile phones are even split between Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android.

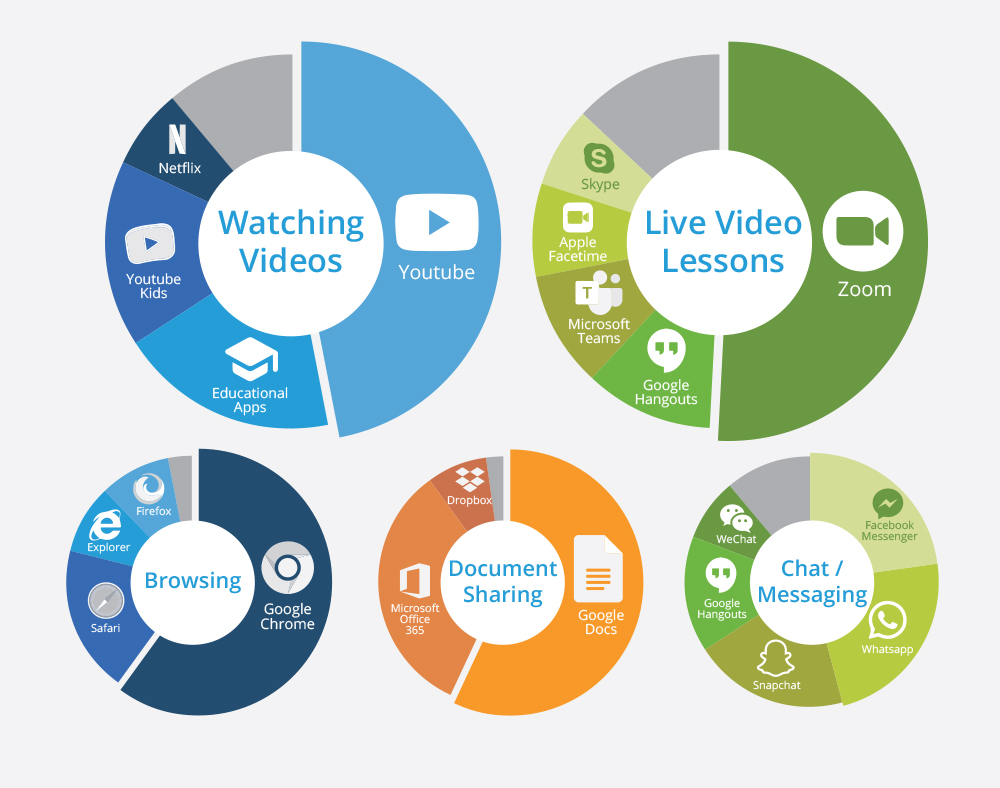

Software usage: applications

A wide array of software is used for different online learning tasks. The educational software market is particularly diverse. However when it comes to common tasks, there are clear commercial frontrunners such as Zoom for live video lessons and YouTube for watching videos. The most common browser is Google’s Chrome.

Types of activity

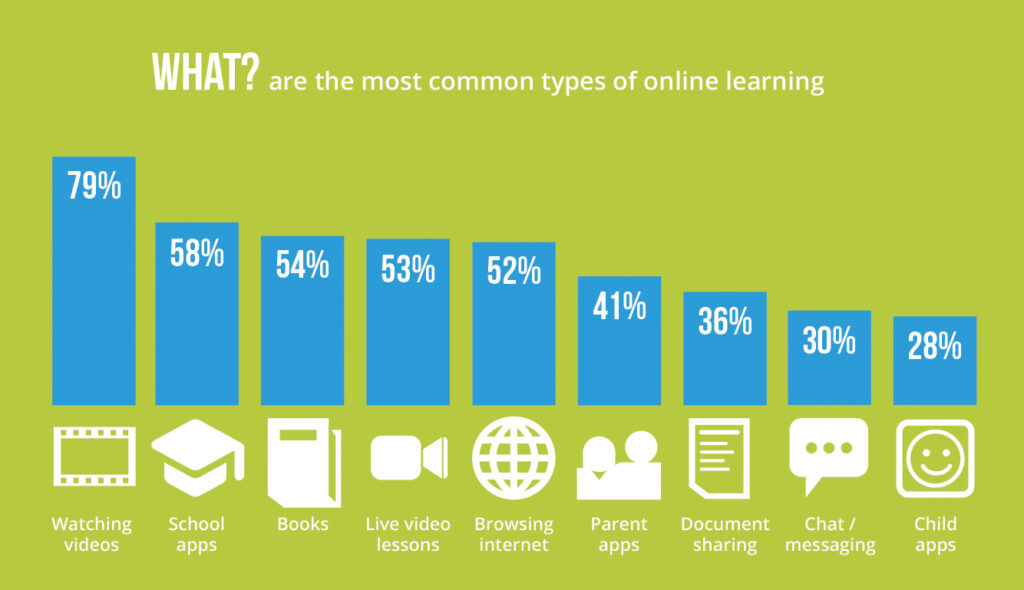

The most common form of online learning across all ages is watching videos. Three-quarters use school apps. Beyond that there are significant variations across age groups as children mature: younger children (under 5) read far more books on their devices; whereas older children (14+) browse the internet and use online chat much more. Those in the middle do much of their online learning through school approved or mandated apps.

Parental concerns

The most common parental concern across all age groups is that their children will see inappropriate content, followed by talking to strangers. Beyond that, concerns are largely age specific: online bullying fears are most pronounced in 11-13 year olds; learning unsupervised in a significant concern for 5-7 year olds; and parents of children 14+ are more concerned that they are not building a real sense of understanding from online learning. Parents of 8-10 year olds feel that group is at most risk overall.

Parental controls

Over half of all parents use parental controls of some type, and most of them use the

controls that are provided through the device’s operating system i.e. those provided by Apple, Google and Microsoft.

However a wide range of other controls at every point in the information path are used: from controls provided by internet service providers to content controls on internet routers to app-specific controls to special software whose sole focus is to provide additional online safety.

Every system operates independently with few common categories or standards, making it confusing for parents. Nevertheless, most parents are mostly content with the end result.

Just over a third of parents said parental controls “work great” while another third said they were “ok.” A fifth said there were “better than nothing” and just five per cent felt they were “more of a hindrance than a help.”

When it comes to ease of use, there is slightly less satisfaction: there is a drop of six per cent of parents who think controls “work great” to those that say they are easy to set up.

There is a corresponding rise of eight per cent of those that said they were “fine.” Overall however most parents seem content.

Of those parents that do not use any form of parental controls, the most common explanation for why they do not use them is that they have never felt the need, followed by a sense that they don’t want to control their children too much.

SURVEY RESULTS: By age group

Under 5s

The under 5s group provides the most clear-cut and consistent answers from parents when it comes to online learning and safety.

The under 5s group provides the most clear-cut and consistent answers from parents when it comes to online learning and safety.

A majority (54 per cent) use tablets as their primary device and of them a majority (55 per cent) run Apple’s iOS operating system i.e. 30 per cent of under 5s use iPads for online learning. That does still leave a significant number using other devices and operating systems however. For example, eight per cent use Windows laptops and nine per cent use Android phones as their primary devices.

By far the most common form of online learning for this age group is watching videos (79 per cent), with the next most common being books (49 per cent) and apps that parents have downloaded (45 per cent) .

Given the cognitive and social skill levels of children under 5, it is not surprising that document sharing and online chat are rarely used. But even at this age, 35 per cent of parents said that their children take live online lessons: pointing to a very specific shift brought about by the coronavirus pandemic and social distancing.

A majority of parents – 62 per cent – used some kind of parental controls, with three-quarters using the device’s own controls: in the case of iPads, Apple’s Screen Time controls. Just under a third also install a specific app to provide additional parental controls.

In the specific case of under 5s using an iPad, parents are largely happy with parental controls with ease of use scoring 4 out of 5, with a lower score of 3 out of 5 when it comes to effectiveness.

Many parents expressed the same thought: that parental controls weren’t strictly necessary at this age. “I don’t need parental controls if I’m paying attention to them,” one told us. Another: “[My child] is too young to really know how to go on things. When she’s older I will put a parental lock on things.”

Just under half of the parents say their main concern is their children seeing inappropriate content, with a fifth highlighting talking to strangers as their biggest worry. This age group is the largest user of the restricted version of YouTube, YouTube Kids, with 28 per cent of parents saying it is the main source of video content that their child watches.

When she’s older I will put a parental lock on things

Ages 5-7

This age group uses tablets and laptops in roughly equal numbers. A third of tablets run a version of Android and two-thirds iOS; and laptops are split roughly equally between Windows, Mac OS and Google, making this group the most diverse in terms of devices.

The most common online learning tasks are the same as under 5s – videos and books – but with children of this age going to school for the first time, the use of school apps comes a close third with 61 per cent.

There is still a significant degree of hands-on parenting at this stage, with 50 per cent of parents saying that their child uses apps that they have installed (as opposed to their child). And this age group contains the largest number of parents that have installed a specific parental control app (42 per cent). During those installations, parents also take advantage of parental controls that exist within the apps themselves more than any other group.

In terms of concerns, learning while unsupervised and talking to strangers are most pronounced as 5-7 year olds learn how to read, spell and navigate their devices and the internet for the first time.

In the specific case of this age group using an Android tablet, parents are happy with parental controls with both ease of use and effectiveness scoring 4 out of 5.

However with a more complex use of devices at this age group, signs of frustration with parental controls show through. “Most parental controls are either far too strict or far too lax. It would be nice to have more micro-control inside sub areas to be able to dial in exactly what I would like my child to be able to have access to or be denied from,” one told us.

Another said: “I’m too often notified about irrelevant or unimportant things which causes me to ignore or overlook the more useful notifications.”

Most parental controls are either far too strict or far too lax

Ages 8-10

This age group is the first to move away from tablets toward laptops: 44 per cent versus 30 per cent. They are also the largest uses of desktop computers (18 per cent), likely reflecting use of a family computer as they move away from tablets.

Windows is the most common operating system for desktops (42 per cent) and within that group the differences in using an older device format are clear: 81 per cent of them have dedicated parental control software (as opposed to 67 per cent for the age group as a whole) and concern that a child will download something dangerous as the primary concern jumps to 27 per cent, almost eclipsing the universal concern of inappropriate content (at 30 per cent).

Parents of this age group appear most concerned in general about online safety, with 67 per cent of them having some form of parental controls, and many using multiple layers of controls. Although talking to strangers is a concern at all age levels, it is most pronounced at this age, with 29 per cent of parents saying it is their primary concern. Online bullying also starts to come into play.

Despite the higher overall level of concern, parents are however relatively content with how effective parental controls are, giving an average of 4 out of 5, with ease of use dropping to 3 out of 5, possibly as a result of the fact that parents are trying to cover more bases as their children increasing start using document sharing, browsers and chat.

“I use many different types of controls because no one solution meets all of my needs,” explained one parent.

There is a notable increase in parents concerned about their children’s online safety for 8-10 year olds. “I’m scared when my child is online,” one parent told us. Another: “Safety is of upmost importance.” And another expresses satisfaction at the “ability to monitor all activities from my remote device.”

But there remains a persistent level of unhappiness over how parental controls work and a lack of granularity: “I don’t really understand them,” said one parent, “and worry that if he needs to use the Internet for research his search responses will be limited because of the controls.”

Safety is of upmost importance

Ages 11-13

There are several notable peaks for children aged 11-13 when it comes to online learning: they are the largest users of both live video lessons and school apps across all age groups.

They are all the group that uses both laptops and mobile phones more than any other group, strongly suggesting that they are given their own electronic device as their online use across all activities grows. Browsing the internet becomes the second most common form of online learning and activity for the first time (watching videos remains the frequent activity.)

Parents become significantly less concerned about their children talking to strangers and much more concerned about online bullying, as the pre-teens spend more time within their peer groups. Hand-in-hand with that comes a large increase in the use of online chat, particularly on mobile phones. When it comes to school apps, for the first time homework sharing apps take the top spot above maths and readings apps.

As children become increasingly autonomous, especially over their own devices, the number of parents that say they have parental controls in place falls. There is however a notable peak in the percentage of parents who install parental controls on their internet routers (25 per cent) and use their service providers’ parental control services (also 25 per cent). Those are both things over which they have control and through which internet traffic has to pass.

When it comes specifically to mobile phones, however, parents are significantly less happy with how effective such controls are, scoring just 2 out of 5 in effectiveness and 3 out of 5 in ease of use. More parents in this age group than any other have suggestions for how parental controls can be improved, including ways of tracking activity, receiving more alerts and looking for clearer explanations for how the controls work.

Many parents noted that they had had discussions with their children about how to stay safe online at this stage, as well as expressed confidence that they could be trusted. But others expressed how their 11-13 year olds had become sufficiently tech savvy to bypass many controls.

“Being able to see what my child is looking at during all times is very useful so they cannot delete their history later and hide things from me,” said one parent. Another worried that it “is very hard to get a good balance between reasonable parenting control and privacy invading.” And another was frustrated at how inflexible some controls are: “The kids constantly come to us to use something that is restricted but really shouldn’t be.”

Being able to see what my child is looking at during all times is very useful so they cannot delete their history later and hide things from me

Ages 14+

At this stage, the young adults in the household are often as tech savvy, or more so, than their parents. Laptop usage is highest, with a fairly even split between Windows, Mac OS and Google (Chromebooks).

Browsing, document sharing and online chat is more frequent than any other group, although when it comes to online learning schools apps are still the most frequent activity (after watching videos of course). As with all the older age groups, Google’s Chrome browser is by far the most used software to access the internet.

Parents continue to use parental controls but to a much lower degree (just 41 per cent); of those that don’t, 65 per cent of them say that they just don’t see the need. Those that do use parental controls, just less than half of them use the controls that their internet service provider or mobile operator provide, making it by far the largest across age groups. While seeing inappropriate content still sits at the top as the number one concern, in second place comes the fear that their children are not really learning as well through online lessons as they would in a physical classroom.

Somewhat unusually, while there are more parents expressing that they are very happy with the effectiveness of parental controls, there are also a larger number than in younger groups saying they are not happy with how effective they are, resulting in an overall 3 out of 5 score. Likewise, ease of use gets a lower-than-average 3 out of 5.

Many parents at this stage note that they think it’s more important to teach their children how to be safe online rather than try to block or limit content. “There’s a danger some parents who aren’t very tech savvy, or perhaps lack tech confidence, will use [parental controls] as a replacement for talking to their kids about staying safe online,” said one parent. “I’ve also known friends of my son figure out how to disable them – they’ve been a lot more savvy than their parents. I think they can play a role in educating your kids while keeping them safe, but shouldn’t be used as a replacement for dialogue, nor as a way for parents to feel less anxious or convince themselves they’ve done all they need to.”

“Kids can find ways around,” notes another. “Older teens find ways around parental controls,” says a third. The issue of controlling content at that stage can also become a source of tension. “I feel I can trust my child to talk to me about issues,” said one parent. “They’re pretty unnecessary, your child will lose trust in you,” said another.

SURVEY METHODOLOGY

We developed a survey targeted at parents that gathered information on two main topics: first, how children were carrying out online learning, through what devices and which software; and second, what parental concerns were, what controls they had in place and how effective they felt those controls were.

You can see the full survey at the end of this report. The survey contained a significant amount of internal logic that limited the questions they saw based on earlier responses.

For example, only those parents that said they did not have any parental controls were directed to the question that asked them why, and they also skipped over any questions related solely to parental controls. Likewise, only if a parent selected a specific activity do they see the follow-up question asking them what software their child uses for that specific activity.

Audience selection

We used SurveyMonkey’s targeted responses service to gather the majority of the 1,173 responses. We ran an initial test on the service, resulting in 362 responses and carefully analyzed the results to check their quality.[efn_note]Among other things, we varied answer-position between static and dynamic to check that respondents weren’t just clicking on the first response each time. Many questions only appeared in response to an earlier question and we checked whether these additional questions were answered and whether they were consistent with answers given by the same individual. We checked what was typed into open-ended response boxes to see if they were consistent with other answers. And we included a gateway question at the very beginning of the survey to ensure that only those who self-identified as parents would see, and could respond to, the rest of the survey. The result was a high level of confidence in the quality of responses provided by SurveyMonkey’s targeted response service.[/efn_note]

Confident that the results were from real, individual parents who had answered honestly and in-depth, we then expanded the survey to both the US and UK, resulting in a further 799 respondents (345 from the US, 454 from the UK). We also took out ads on Facebook and promoted the survey on IFFOR’s social media channels resulting in a further 12 responses.

Demographics

Respondents to the survey represented a broad cross-section of society, adding to our confidence in the end results. We also included a question (“How tech savvy do you consider yourself to be?”) to the survey to check how representative respondents were of the broader population: since it was an online survey (albeit one that worked just as well on a mobile phone as a desktop computer), we suspected that respondents would be more technologically literate than the general population.

The result of that question was that 40 per cent of respondents described themselves as “very savvy” about technology, 54 per cent as “about average” and just 6 per cent as “not savvy at all.” The conclusion we drew from this is that the respondents were more technologically literate as a whole than the general population. But not to the extent that it impacted the validity of the results.

Respondents covered all age groups of children evenly: it varied from 17.8 per cent for 14+ to 23.9 per cent for under 5s (the others being 18.7 per cent, 20.2 per cent and 19.6 per cent). The perfect result would have been 20 per cent of each of the five age groups, but the degree of variance in our survey is small enough to be insignificant taken overall.

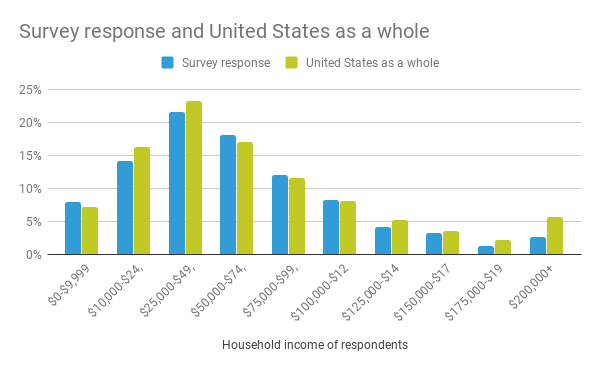

There was a relatively even split in the gender of parent respondents: 43 per cent male; 57 per cent female. Household income from respondents in the United States closely aligned with the United States as a whole (using US Census data), with 7 per cent of respondents saying they preferred not to answer. And respondents were geographically spread across both the US and UK.

Taking all these factors into account, we are confident that the survey results are fair, accurate, statistically relevant and representative of the population as a whole.

WHO DID THIS WORK

The International Foundation for Online Responsibility, or IFFOR.

IFFOR is an independent policy body that was formed to develop registration and abuse

policies for the .xxx registry and has gone on to develop and publish guidelines, policies and educational materials around the topic

of online content.

IFFOR is funded in large part by internet registry operator Minds+Machines, a public company listed in London, which operates more than 20 internet registries including .london, .law, .yoga, .wedding and .work.

For this project, we pulled together a team of educational and policy experts to form a Policy Council. They are:

Fiona Alexander

Fiona Alexander is co-founder of Salt Point Strategies and Distinguished Policy Strategist in Residence at American University.

A former government executive with extensive experience in international Internet, telecommunications and emerging technology

policy, she served at the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) in the US Department of Commerce for close to 20 years.

At NTIA, she managed the US government’s relationship with ICANN and is NTIA’s sole Presidential Rank Award winner for her leadership in the privatization of the Internet’s domain name system.

Fiona was also the convener and co-leader of the Department of Commerce’s Internet Policy Task Force which developed policy, norms and tools for issues related to commercial data privacy, online copyright protection, cybersecurity, and the global free flow of information.

Chad Anderson

Chad Anderson is an attorney practicing in business relations, privacy and data security and is the founder of DPO Solutions Ltd which provides data privacy policy consulting. He earned his Juris Doctor at the University of North Dakota and Master’s in Cybersecurity Law at the University of Maryland School of Law. He is actively licensed to practice before the Supreme Courts of Iowa, Arizona, Nevada and the United States Supreme Court.

Chad earned bachelor’s degrees in Accounting and Economics at the University of Northern Iowa, and holds IAPP certifications in EU privacy law and privacy management (CIPP/E and CIPM). Chad sits on the Arizona State Bar Ethics Advisory Group and is a member of the Cybersecurity section of the American Bar Association, the Information Systems Audit and Control Association, the International Association of Privacy Professionals, and Mensa International.

Sharon Girling

Sharon Girling OBE is a former police officer who retired following thirty years’ service. Her final role was as an investigator and child protection lead at the Child Exploitation and Online Protection Centre (CEOP). She was at the forefront of a national and international response to online child abuse and developed the processes and procedures that led to the creation of CEOP where she was a founder member.

She is currently conducting training programmes for schools, law enforcement and businesses both nationally and internationally. Sharon is the Safeguarding Assurance Manager for a Fostering Agency with more than 1000 carers. She has been awarded an OBE by Her Majesty The Queen for her services to child protection and policing.

Emily Taylor

Emily Taylor is CEO of Oxford Information Labs. A lawyer by training, Emily has worked in the Internet governance and cybersecurity environment for more than 20 years. She has served on major ICANN reviews of security, policy development and privacy, the UN Internet Governance Multistakeholder Advisory Group, Global Commission on Internet Governance research network, and as director of Legal and Policy for Nominet.

Emily is an associate fellow with the International Security Department at Chatham House in London and editor of the Journal of Cyber Policy; she is a research associate at the Oxford Internet Institute and an affiliate Professor at the Dirpolis Institute, Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies, Pisa. She is a graduate of Cambridge University, qualified as a solicitor in England and Wales (now non-practising), and has an MBA from Open University.

APPENDIX: Survey

We used an online survey to gather responses. Here is a long-form version of it as a PDF.